After the initial brilliant idea to spend a weekend in Berlin with Felix and spend a day at the Kathe Kollwitz gallery, it was a wrench to leave Scotland and my studio knowing that I would be away for 5 whole days. I pack sketch books, inks, pens and watercolours. I pack more reading material than is possible to get through in 5 days. There is a sense of insecurity about keeping focussed whilst travelling. I know that this is a waste of energy. I am always more alert when I am on the move; – connections are made that are not made when I am comfortably static in my environment.

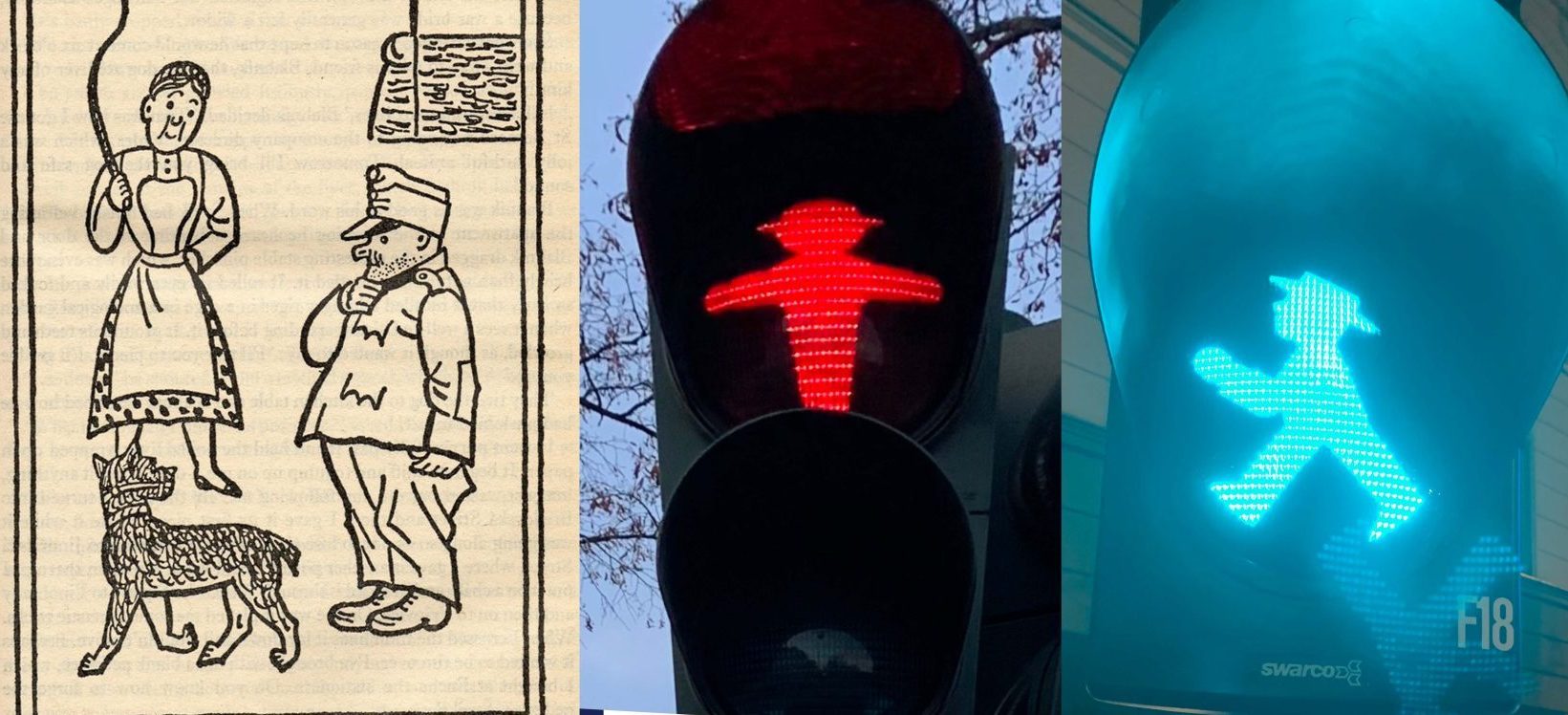

Berlin is particularly stimulating because of its fluidity. Here the sense of previous lifetimes and political movements is palable. The generations of activities of human beings are layered on top of each other, all leaving traces, marks and stories that tell us that we too are transient. The earth’s skin has been built upon, fought upon, dreamt upon and allowed to crumble and reclaim itself a little. The pelican crossing characters in some parts of the city are recognisable as GDR icons. The good citizen walking when he is told to and stopping when he is asked. I remember Good Soldier Schweik, the simpleton soldier that avoids all hazardous activity and runs rings around his superiors. Berlin makes me feel a little like that. Free but dodging less comfortable times and places.

The visit to the Kathe Kollwitz museum feels like a pilgrimage. Kollwitz (no, I’m going to call her Kathe, she is a friend) has inspired me for a good number of years. It is interesting to feel excited again about the future and revisit Kathe’s work with fresh eyes. Previously I have looked to her for political inspiration, now I am looking for the quality of her mark making. I am wondering how she makes her prints. Why does she switch from woodblock to litho to etching and to what effect? I learn that Kathe initially made etchings before moving to litho because it was more immediate and then to woodblock for its associations with political activism. Her drawing is visceral. The physical struggle against oppression and death and even the embrace of death as a release from suffering, is real, on the paper, before our eyes. The very sinews of the woman being dragged away from her young child by death makes me shudder. I feel I understand the struggle I am seeing, not just the woman desperate to live but also the artist putting everything she has into the drawing of the mother and the child, for us, for her?

The faces of the children echo the tenement children of Joan Eardley – or the other way around. Did Joan Eardley learn from Kathe Kollwitz? I am weakened by the lives echoed around me and find a chair to sit and contemplate. Felix’s girlfiend Nata joins me to ask how the work is made. We don’t talk about the suffering that we are seeing. We talk a little about the representation of war in general. I wonder if I should refer to her home, Ukraine, being subject to untold violience. I decide not to.

Later Felix tells us that he has a plan to go the ukraine with Nata and visit her grandmother whom she loves deeply. He would like our opinion. Simon tells him that he respects and admires his wishes. I say that it is not the place of parents to block their adult children’s need to live fully in the world, no matter how anxious we may be. I am not sure it is my place to make any comment. As much as I love Felix dearly, I did not give birth to him. I think of Kathe Kollwitz and her dead son, all of those mother’s of soldiers. Felix’s plan sounds sensible and the risks are negligeable. But I am left with a cold shiver wrapped around my spine.  .

.

.

.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.